1.1 Reading and cognitive processing challenges

Cognitively speaking, reading is a lot of work—it involves both decoding and understanding text. First, a user has to “decode” the text by assigning meaning to the words. Next, a user has to comprehend the text by stringing the words together to understand what the author is trying to communicate in a particular sentence or paragraph.1,2,3

Users with limited literacy skills have more problems with short-term and working memory than users with higher literacy skills.4 They may struggle to decode challenging words and remember their meanings.3 If a webpage has a large amount of content, users may not be able to remember it all. Furthermore, what they do remember may not be the most important information.

Users with limited literacy skills often describe themselves as reading well or very well.3,5 However, data from eye-tracking and usability studies paint a different picture.

According to these studies, users with limited literacy skills generally read more slowly, and reread words, sections, or elements on a website (like buttons or menus) in order to understand them.3 And depending on the situation, limited-literacy users may:

- Skip words or sections, or start reading in the middle of a paragraph3,7,8,9

- Try to read every word because they can’t effectively scan and draw meaning from content3,7,10—this is more common when users are reading something very important and they feel the stakes are high

These strategies used by users with limited literacy skills reinforce the importance of creating simple content that won’t overwhelm readers with too many words. Dense “walls of words” can trigger limited-literacy readers to skip content altogether—or they may try to read every word on the page while struggling to understand what they’re reading.

Additionally, online forms present a unique set of challenges for limited-literacy users. Users need to read the instructions and the form field labels, and then either spell the answers to questions or read and select from multiple-choice answers.3 This is a lot to ask from users with limited literacy skills.

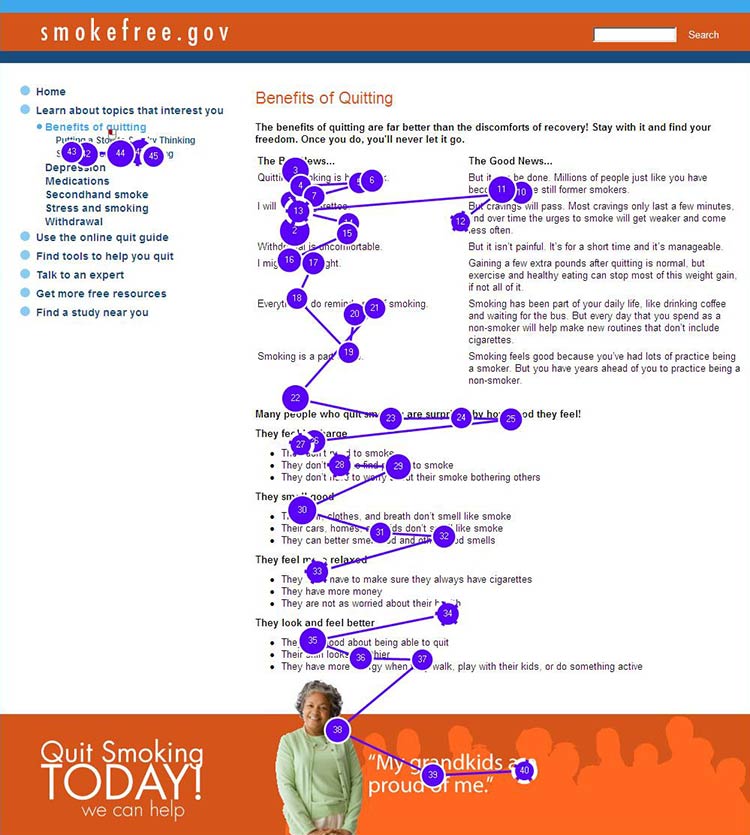

Gaze path of a reader who does not have limited literacy skills skimming a page.

Source: Colter, A., & Summers, K. (2014). Eye Tracking with Unique Populations: Low Literacy Users. In J. Romano Bergstrom & A. J. Schall (Eds.), Eye Tracking in User Experience Design (pp. 331–346). Waltham, MA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers/Elsevier.

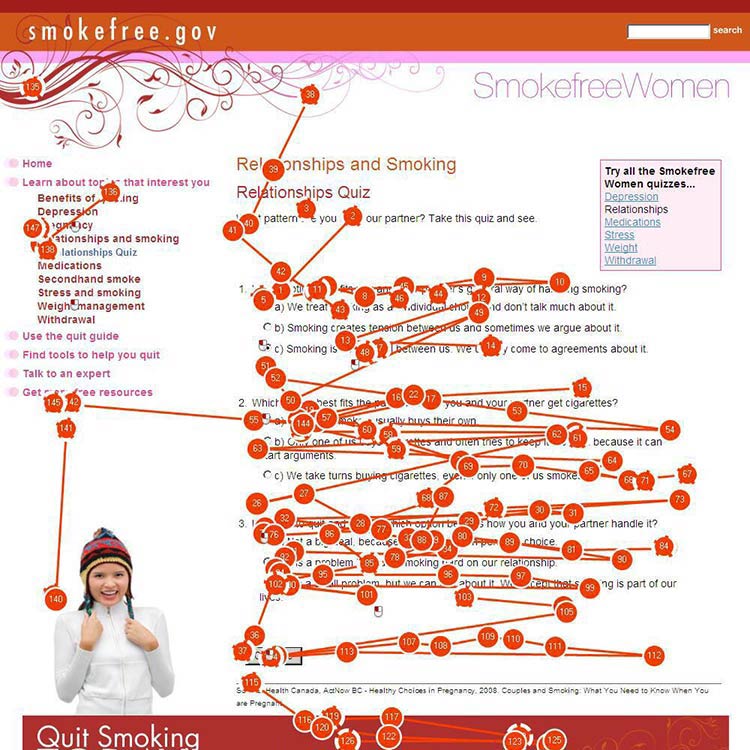

Gaze path of a user who has limited literacy skills reading (and re-reading) every word.

Source: Colter, A., & Summers, K. (2014). Eye Tracking with Unique Populations: Low Literacy Users. In J. Romano Bergstrom & A. J. Schall (Eds.), Eye Tracking in User Experience Design (pp. 331–346). Waltham, MA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers/Elsevier.

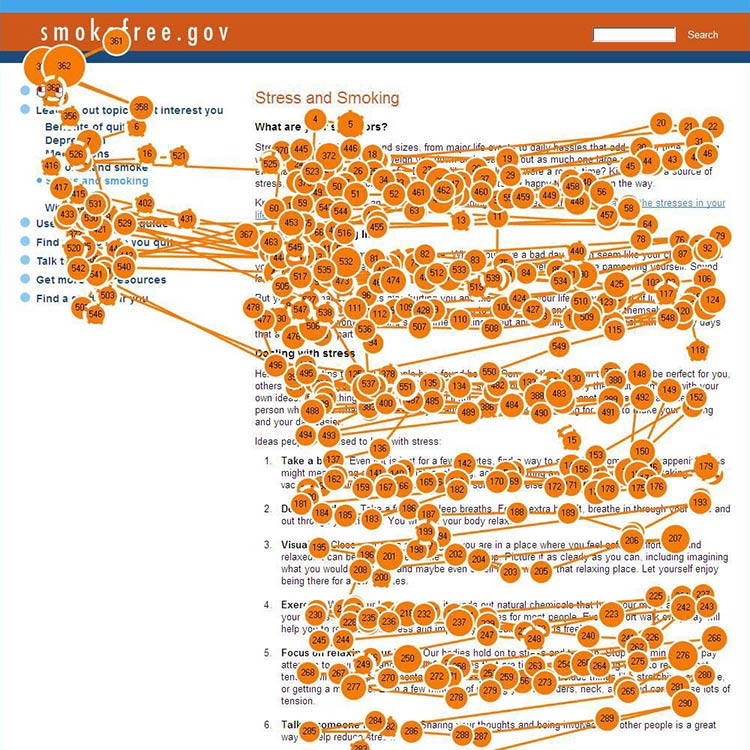

Gaze path of a user with limited literacy skills reading only the text that looks easy to read.

Source: Colter, A., & Summers, K. (2014). Eye Tracking with Unique Populations: Low Literacy Users. In J. Romano Bergstrom & A. J. Schall (Eds.), Eye Tracking in User Experience Design (pp. 331–346). Waltham, MA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers/Elsevier.